Pakistan

The Crisis in Pakistan-United States Relations: Analysis of Recent Events

|

| Supply Trucks, csmonitor.com |

Background

The Recent Politics of the Pakistani Opposition

Post-2014 Afghanistan?

The Next Steps

What should Pakistan and United States do now in Afghanistan?

- They should join hands to broker a power sharing arrangement in Afghanistan. Different power groups in the country, especially the Taliban and Northern Alliance, are brought on the negotiating table for this exercise.

- Intense and coordinated diplomatic activity shall be required for any meaningful intra-Afghan dialogue. These negotiations will surely be tedious but are needed nevertheless.

- Pakistan must facilitate a Taliban-United States deal to the extent possible. The United States work with Pakistan on this one.

- Both hold a series of meetings in Islamabad to chalk out the contours of a viable endgame in Afghanistan.

-

Later, invite other regional players like India, Russia, China, CARs and Iran to contribute their share in

finalising the endgame.There are a number of things for Pakistan to do immediately:

1. Convince the US that Pakistan knows Afghanistan like no other and therefore must be trusted to play a key role in the endgame. A number of Confidence Building Measures (CBMs) are suggested:

a) Renounce the old discredited policy of ‘Strategic Depth’ and ‘a friendly Western border’ propounded by the Pak Army. Most importantly, the Zardari Government must wrest control of the Afghanistan policy from the hands of the military. It must immediately announce a stopping of support for the Haqqani network and the Lashkar-i-Taiba. Pakistan must engage the United States which is counting on it to help convince the Taliban and other groups fighting the Afghan government to halt violence and enter into a political dialogue.

b) Stop the Defa-e Pakistan Council from going overboard in protesting against the United States.

c) Joint efforts with the United States to tackle the Islamic extremist problem.

- Stop covert CIA activity in Pakistan

- Reach out to the Pakistani Civil Society in a new effort at ‘winning hearts and minds’.

- Acknowledge that some past actions are responsible for a great deal of animosity among the Muslims.

- Support the Palestinian cause and stop Israeli military subjugation and occupation of Palestine.

- Support a final solution of the lingering Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan

- Openly support Pakistan in taking a final and decisive military campaign against terrorist’s hideouts in North Waziristan. Remember the Pakistan Army is exhausted and badly stretched to do this alone.

- Stop threatening Iran over the nuclear issue. Give diplomacy a fuller chance.

- Release the stuck up CSF money to Pakistan.

Dr. Sohail Mahmood is the Chairman of Department of Politics & International Relations, International Islamic University, Islamabad, Pakistan

Pakistan

‘No More!’ The Geopolitical Impact of Souring Relations Between the United States and Pakistan

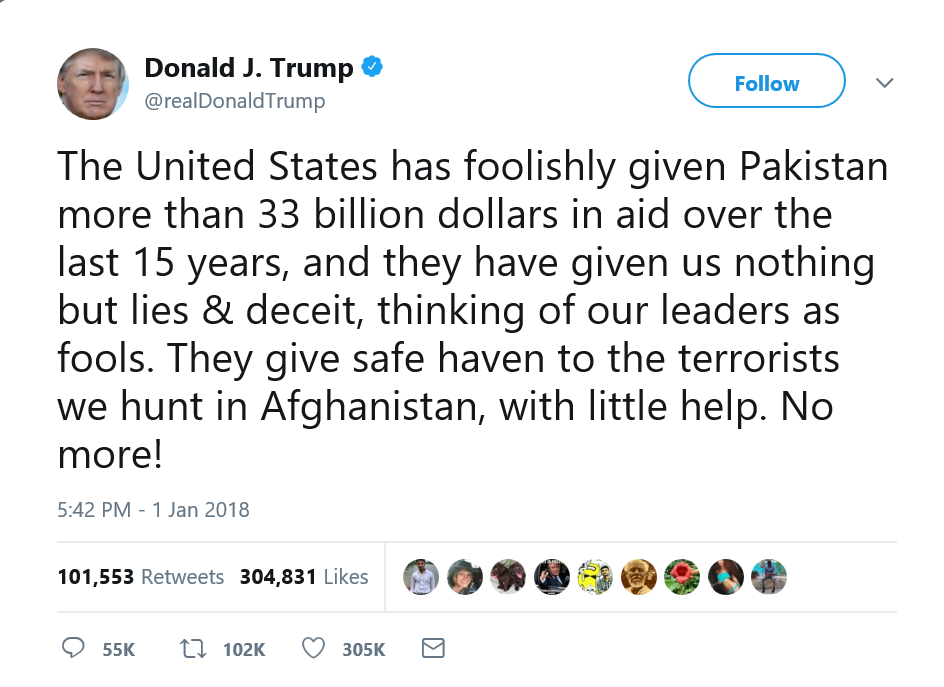

A Donald Trump led the United States of America bade farewell to the year 2017 in isolation after the contentious Jerusalem issue saw the rest of the world stand united against them in a historic resolution at the UN. They went away with the promise that this stand against them would be remembered by them when the international body, as well as many other countries, looked towards them in their time of need. Now, the USA still seems unfettered in its approach towards having its way on matters of priority as it looks set on losing a long-standing ally in Pakistan. The issue at hand is of the billions of dollars that Pakistan has received in aid from the US to help fight against terrorism in the middle east and the country’s alleged inaction towards the same.

A New Year Resolution: As it happened

Trump’s first tweet of 2018 went as follows. “The United States has foolishly given Pakistan more than 33 billion dollars in aid over the last 15 years, and they have given us nothing but lies and deceit, thinking of our leaders as fools. They give safe haven to the terrorists we hunt in Afghanistan, with little help. No more!” Then, on Thursday, the U.S. State Department announced that most of the security assistance to Pakistan will be suspended unless there is decisive action on their part against the various militant groups on its soil. The US has already withheld $255 million in military aid to Pakistan, and this move paints a picture of rapidly deteriorating ties between the two countries that have been allies ever since Pakistan was born in 1947.

In response to the allegations and the remarks, Pakistan Foreign Minister Khwaja Asif has said that the country is “ready to publicly provide every detail of the US aid that it has received.” He also added, “We have already told the US that we will not do more, so Trump’s ‘no more’ does not hold any importance.” The Pakistani ambassador to the United Nations Maleeha Lodhi also chimed in at the international body earlier in the week, ” We have contributed and sacrificed the most in fighting international terrorism and carried out the largest counterterrorism operation anywhere in the world.” She added, “We can review our cooperation if it is not appreciated.” The tone is clear. Pakistan does not look like it is willing to bow down to Trump and as far as the cut in aid is concerned, it is not easy to estimate exactly what the amount is in question. Current estimates put the figure at over $900 million. It is also important to keep in mind that the aid to Pakistan in question has already been deteriorating over the years.

So is there enough reason for Pakistan to be worried?

It’s then worth a look whether this move by the US is enough in itself to make Pakistan act the way it wants it to. More importantly, how much is Pakistan likely to suffer, if at all, from the announced cut in the aid? Despite, the Prime Minister Shahid Khaqan Abbasi’s claims that the aid from the US does not amount to much today, experts believe that the cuts will cause short-term problems for the Pakistani military. “It will also be a setback in the long term as China or any other friendly country cannot totally replace the resources that Pakistan needs to keep its military machine well oiled”, says Prof. Hasan Askari Rizvi, a defence analyst and author of ‘Military, State and Society in Pakistan’. As cooperation between the two countries looks increasingly unlikely, critics of Pakistan’s inaction have also called for stripping of the nation’s title as a non-NATO ally and imposition of sanctions to coerce them into following the US vision.

The risks involved with tough measures

It is important to remember however that the US is dealing with a double-edged sword here. In recent years Pakistan has tried to make it clear that it is not as dependent on the US as many would make it seem. Pakistan is still the key to most of the involvement of the United States in Afghanistan since it controls most of the supply lines for the transfer of material into the country. Should Pakistan deny the US access to these lines, the US may face a six-fold increase in costs to over a $100 million in order to move military equipment and personnel into Afghanistan.

The US does not want instability in Pakistan since that could have drastic consequences for the region. Perhaps it is for that reason that they’re still providing Pakistan with non-military aid, albeit more carefully. Neither does Pakistan want a situation where it is completely cut off from the United States for that could deal a severe blow to them in their attempts to portray themselves as a more responsible nation and check India’s power in the subcontinent. However, should the matter at hand take a turn for the worse, the US won’t need a second invitation to pursue a more aggressive approach in the region with more involvement from India and Afghanistan. Pakistan, on the other hand, will almost certainly have the backing of its all-weather ally China in countering the move to maintain a power balance in South Asia when the game is afoot for a new geopolitical competition, with the same old motives.

India

Struggling over Water Resources: The case of India and Pakistan

flickr/lensnmatter

Have you heard about conflicts over water? Have you ever wondered how hard it is to ensure water access in a conflicted area? Well, what I can tell is that you have certainly heard how people are dying from thirst and hunger or how they getting sick because of lack of water. What you might not know is that sometimes it is hard to ensure adequate access to water. What are the reasons? In fact, there are many, but this article will focus on one of the reasons: a conflict. We will take a specific example of India and Pakistan, explain the reasons for the water dispute and evaluate the current situation with water resources.

To begin with, do you know that it has been only seven years since the recognition of the right to water and sanitation? Before that there was a long debate whether this right exists at all. Neither the 1948 Universal Declaration on Human Rights nor the 1966 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) address water. Not earlier than 2010, the United Nations General Assembly and the Human Rights Council have finally adopted resolution which recognized access to clean water, sanitation as human right (GA/10967).

To ensure this right is not an easy job. First of all, water situation in some regions is aggravated by its geographic position. Increasing population, the impact of economic development, climate change only makes it harder. These factors results in scarcity of fresh water. Moreover, water has another quality that makes it even more significant – its irreplaceability. Secondly, some regions are additionally involved into conflicts which make access to water more difficult. What makes it even more complicated is the fact that many river basins and aquifer systems are being shared by different states.

When something is shared, it sometimes gives precedent to a dispute. In case of two countries, it definitely does. This is the case between India and Pakistan which share the Indus basin. Currently both countries are experiencing lack of water, whereas water demand is rising and water resources of the Indus River continue to deplete. Some say that the situation in Pakistan is even worse, where the flow of river is dropping at seven percent yearly (See Baqai 2005, at 77). Thus, the river basin is giving rise for a dispute. Given the history of long-rivalry, it may result into a war.

The water dispute between Indian and Pakistan dates back to the early 20th century, but at that time it was a provincial conflict over the river to be resolved by British India. In 1947 India and Pakistan were partitioned, and the natural borders of river Beas, Chenab, Jhelum and Sutlej have been neglected. Many dams stayed in India, while their waters irrigated a major part of Pakistan. The geography of partition left the source rivers in India, and Pakistan felt threatened by its control. Moreover, the situation with Kashmir presented additional difficulties. Apart from its strategic value, the Eastern waters of Kashmir are significant for Pakistan in terms of resource access (its irrigation system largely depends on it).

Soon after the partition, a major crisis occurred when the Government of the Eastern Punjab (India) took its sovereign rights over the territorial waters and blocked Sutlej river, stopping water flow to Pakistan and causing agriculture of Pakistan severe damage. This precedent stayed in the collective memory of Pakistan, leaving fear that India could repeat its actions. India yet claimed that it was caused by Pakistani actions in Kashmir. Even today Pakistan feels insecure by its neighbour’s power over the Indus river.

By 1951 the conflict became more dangerous as both states refused to discuss the matter. That’s why, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (today’s World Bank) was approached to mediate the conflict. It was not until 1960 when the parties finally reached an agreement and signed the Indus Water Treaty (IWT).

To ensure the best solutions the Permanent Indus Commission represented by both sides was established. Until 2015 the meetings were held regularly once a year to resolve problems, but after that none of them happened because of the tensions in the relations of India and Pakistan.

Only in March 2017 the meeting took place with Pakistan welcoming the Indian delegation. The World Bank was asked again to intervene but it refused, leaving two countries for a face-to-face dialogue. Even though the meeting did take place, it was decided to suspend further talks.

The current water dispute between two states is shaped by the following factors. First of all, it is fast growing population rate which puts enormous pressure on resources. Secondly, there is inefficient and inadequate use of water resources as well as increased demand for water as a result of economic growth. Thirdly, water stress is becoming more severe and it is further aggravated by climate change. Apart from this, one can see a reason for a dispute in inability and reluctance of political leaders of India and Pakistan to resolve the issue. As it is heated by the public opinion from both sides, the issues continues to be on the agenda. Additionally, there are grievances caused by the IWT which influence the dynamics of the dispute.

However successful the Indus Water Treaty may be, it remains to keep low profile and failed to reach its full potential. Both parties did agree on a partition of the Rivers, yet they did not pay specific attention to the other challenging parts of the agreement such as optimization of the use of the Indus waters (Chari 2014, at 5). Further, there is little information in regards to the groundwater use. It also does not address such issues as the division of shortages during dry years and technical specifications of hydropower projects of India, particularly impact of storages on the flows of the Chenab River to Pakistan [1].

Such weaknesses of the Treaty are consequently becoming a source of tension. It gives space for different interpretation, and this is used by both countries to their advantage. The IWT lacks its dynamics towards water resource sharing and has to be adjusted accordingly. Though the Indus Water Treaty did prevent a possible escalation over the water resources, it did not foresee the future depletion of the Indus River caused by population growth, new developments in industry, and more importantly by climate change and global warming. Back into 1960 it was not well-studied or discussed as often as now, hence, it was not given required attention. That is why many call to rethink the agreement and include new pressing issues into the Treaty.

Moreover, there has been an intensive debate in India to revoke the Treaty. It was the Uri attack that laid ground for it. An Indian analyst of water disputes and geostrategic developments, Chellaney suggested India should draw a clear line between the right of Pakistan to water inflows and its responsibility not to harm its upper riparian neighbour [2]. In response, Pakistan warned that any attempts to review and/or exit the treaty would be deemed “an act of war” [3]. Regardless, the Government of India remained mostly silent. The parties are not willing to cooperate; therefore the ITW is weakened by it.

In September 2016, the Prime Minister of India, Narenda Modi, referring the ITW, said that “blood and water cannot flow together” [4]. It was also stated that only in “atmosphere free of terror” the meeting of Indus Water Commission was possible (Ibid.). India has repeatedly mentioned altering and/or exiting the ITW, although there is no exit close in the Treaty.

It should be noted that in case of a conflict the UN Watercourses Convention of 1997 gives special attention to the “requirements of vital human needs” (Article 10, part 2). International Law Commission clarifies these needs and say that there should be “sufficient water to sustain human life, including both drinking water and water required for the production of food in order to prevent starvation” [5]. This refers to the right to water of individuals, and the fact that States should respect and protect these rights.

Political tensions between India and Pakistan have worsened and made it difficult to settle even water issues. In this sense, the Kashmir conflict is inseparable from a water conflict. Many cooperative decisions were impossible because of parties’ inability to make any progress on the Kashmir question.

There is also a high level of securitization of water issues. To securitize means to construct a certain threat (for example, by means of authority). These threats are being dramatized and usually presented as a high-priority for a nation. Political leaders of Pakistan securitize this issue to the extent that it is described as a threat to national security. That makes a dispute more dangerous because water issues are being constructed as threat to a country.

Pakistan has more than once declared that if Pakistan’s need for water is used by India to pressure them, the country will consider it as a direct threat against Pakistani people. Environmental security is intertwined with the risks of violent conflict, mostly because stress in resources (e.g. water scarcity). It is also usually associated with the growing population rate and inequitable distribution of resources.

Sometimes the Kashmir dispute is also explained through headstreams of the Indus. Indian control over it likely pressures Pakistan especially during dry periods of the year. Indian Power projects in Kashmir (like Baglihar Dam) only make Pakistan to securitize water issue even more and treat it as security problem.

All in all, both countries are experiencing an enduring rivalry in regards to many aspects. This rivalry deteriorates the cooperation on water share issues. A high level of mistrust guards many countries’ decisions, that is why cooperative mechanisms usually fail. Moreover, the water issues are being regarded as a matter of national security that may escalate the situation. As water quality and quantity continues to be influenced by climate change, population rate continues to increase, demand for water continues to rise, and both countries continue to blame and accuse each other… it does not look like countries are ready to have a face-to-face dialogue over water resources any time soon. But let’s wait and see.

References

- P. Chadha, “Indus Water Treaty may not survive, warns UN report” India Water Review, 1 March 2017. Available from [http://www.indiawaterreview.in/Story/Specials/indus-water-treaty-may-not-survive-warns-un-report/2013/3#.WUUusut97IU].

- A. Parvaiz, “Indus Waters Treaty rides out latest crisis” Understanding Asia’s Water Crisis, 15 September 2016. Available from [https://www.thethirdpole.net/2016/09/25/indus-waters-treaty-rides-out-latest-crisis/].

- Dr. Jorgic, T. Wilkes, “Pakistan warns of ‘water war’ with India if decades-old treaty violated” Reuters, 27 September 2016. Available from [http://www.reuters.com/article/us-pakistan-india-water-idUSKCN11X1P1].

- Express Web Desk, “Blood and water cannot flow together: PM Modi at Indus Water Treaty meeting”, The Indian Express, 27 September 2016. Available from [http://indianexpress.com/article/india/india-news-india/indus-water-treaty-blood-and-water-cant-flow-together-pm-modi-pakistan-uri-attack/].

- International Law Commission, “Draft Articles on the law of the non-navigational uses of international watercourses and commentaries thereto and resolution on transboundary confined groundwater” (1994) Part II Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 89. Available from [http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/commentaries/8_3_1994.pdf].

Opinion

Pakistan’s Foreign Policy: It’s time to change

Started on the soil of Afghanistan, when this war crossed the border and came to Pakistan, neither Pakistani government, nor US wants to clear this thing. Regular drone attacks in Pakistan with poor precision and accuracy is haunting the civilians part their opinion from US and Pakistani government, resulting into sympathy and support for extremists.

Now the question is for how long Pakistan’s foreign policy will continue this kind of alliance with US which resulted into over 40,000 deaths, $80+ billion in losses, growing insecurity and mounting fear among Pakistanis. Is this alliance feasible when India, China and Russia are deciding their active role in Afghanistan post US.

Between 2002-2010, US Congress approved $18 billion in financial aid to Pakistan, which they claim that roughly 70% of which has been misused by Pakistan between 2002-07 in other things or in anti India activities. Pakistani people have been questioning their government regarding the money, especially when it comes out from another reports that Pakistan Treasury only received $8.647 in direct financial payments out of total $18 billion approved. This conditional Coalition Support Fund (CSF), which Pakistan receives for assisting the USA is nothing compared to the loss of $80+ billion which Pakistan claims.

Pakistani firefighters extinguish burning vechiles after a bomb explosion in Quetta.(AFP Photo / Banaras Khan)

Ally or Client State?

As we sum up what has been said above, and if you agree to my points then everything suggests Pakistan as a client state of US rather than a US ally. This cold war era style tactics that America has been using in Pakistan needs to be dealt with a change in Pakistan’s foreign policy which is also required for peace in Afghanistan even after the withdrawal of US next year

Change in Pakistan’s foreign policy

Pakistan has to reconsider its policy to suit it well in the region in 2014. Most of the Taliban and Al-qaeda attacks in Pakistan are due to Pakistan’s support to US in war against terror. If Pakistan shifts its policy, this might raise confidence level in Taliban and other terrorist networks. This can be good for Pakistan, but the new players, Russia, China and India, who want to play their roles in the development of Afghanistan will not like this. At this, Pakistan has to think whether it wants return of sponsored government in Afghanistan and let it burn to fuel Pakistan’s internal security or allow an independent government that maintains good relations with everyone including India.

Afghanistan interests both South Asia and Central Asia. neighbouring countries like Tajikistan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan are area of concern for China and Russia and any terrorist outbreak in that region can harm their interests in Central Asia, and similarly it is important for India and Pakistan who have been blaming each other of using Afghanistan’s soil against each other.

Pakistan is not in an easy situation. Pakistan’s priority would be to secure its western borders and concentrate on eastern border with India, which is exactly what it did using Taliban. However, this time India which has been trying to lure Afghanistan providing economic aid, infrastructure development and education to keep Pakistan at bay. With the inclusion of China and Russia, we have to see what happens in Afghanistan. After America, we are talking about what Pakistan, China, Russia, and India will do in Afghanistan. It is a pity that no one talks what Afghanistan will do in Afghanistan.

-

Travel11 months ago

Travel11 months agoImmerse Yourself in Nature: Explore Forest Bathing with a New Guidebook

-

Europe11 months ago

Europe11 months agoBarcelona and Athens: cities that will leave an everlasting impression

-

Technology11 months ago

Technology11 months agoHow Virtual Fly Elevates the World of Flight Simulators

-

Health11 months ago

Health11 months agoExperience in clinical quality: What is it, and why is it important?

-

Business7 months ago

Business7 months agoServiceNow Development Consultancy: Business Process Automation as Disruptive Technology

-

Travel8 months ago

Travel8 months agoEnjoy a luxury holiday in Zanzibar

-

Environment8 months ago

Environment8 months agoThe Future of Fashion: The Rise of Eco-Conscious Brands in the Luxury Market

-

Business9 months ago

Business9 months agoScreen Printing Services: A Beginner’s Guide to Avoiding Mistakes and Maximizing Your Investment